Is It Safe to Stay in the Plaka With Family

Is It Rubber to Filibuster a 2d COVID Vaccine Dose?

Some testify indicates that short waits are rubber, but at that place is a chance that partial immunization could help risky new coronavirus variants to develop

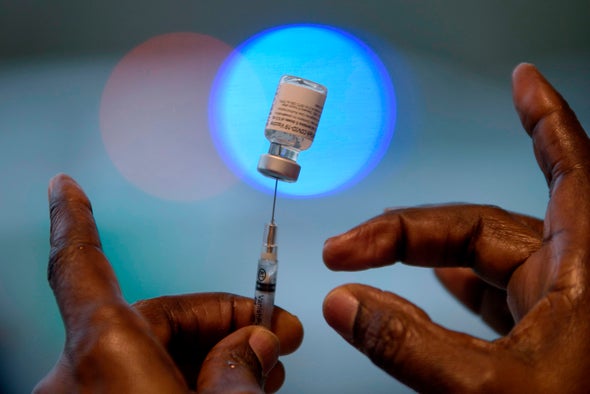

Vaccine shortages and distribution delays are hampering efforts to curb the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. So some scientists take suggested postponing the second shots of 2-dose vaccines to make more available for people to get their first doses. The original recommended interval was 21 days between doses for the Pfizer vaccine and 28 days for the Moderna shots, the two currently authorized in the U.Southward. Now the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has updated its guidance to say that people can expect up to 42 days betwixt doses, though the bureau still advises individuals to stick to the initial schedule. And developers of the Academy of Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine—which is authorized for apply in the U.Chiliad.—advise even longer stretches are possible, saying their shot performs better when its doses are spaced 12 weeks apart. Their data is in a new preprint paper, released before peer review. So what gives? How long can you go on a unmarried shot and withal stay safe? And what happens if your 2nd shot isn't available on fourth dimension? Scientific American explores the potential risks and benefits of delaying vaccine doses.

Why do you demand ii shots?

Vaccines are designed to create immunological memory, which gives our immune system the ability to recognize and fend off invading foes even if we take not encountered them before. Most COVID vaccines elicit this response by presenting the allowed organization with copies of the novel coronavirus's spike proteins, which adorn its surface like a crown.

Two-shot vaccinations aim for maximum benefit: the offset dose primes immunological retentivity, and the second dose solidifies it, says Thomas Denny, chief operating officeholder of the Knuckles Man Vaccine Establish. "You tin think of it like a gradient," he adds. One dose of the Pfizer vaccine can reduce the average person'due south hazard of getting a symptomatic infection by virtually 50 percent, and i dose of the Moderna shot can practise so past about 80 pct. Two doses of either vaccine lowers the risk by about 95 percent.

Why does the CDC now allow upward to 42 days betwixt doses of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines?

The agency updated its initial guidance subsequently it received feedback that some flexibility might be helpful to people, especially if there are challenges effectually returning on a specific date, says CDC spokesperson Kristen Nordlund. While the U.K. is recommending dose stretching every bit a deliberate strategy to get more first shots in more arms, the CDC is suggesting it equally an option to make scheduling second shots less onerous. In the U.South., the vaccine rollout has been painfully slow: two months afterwards the get-go shots were given to the public, only nigh iii per centum of the population has received both doses of a vaccine. And every bit vaccine producers struggle to keep up with demand, experts believe some compromises are necessary to ensure people are fully vaccinated. "Nosotros need to make the all-time conclusion with the resources we have," says Katherine Poehling, a pediatrician at Wake Forest Baptist Health, who is on the CDC's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. "If there'due south plentiful vaccine, information technology might take a different approach than if the vaccine is limited.... But you do demand the 2nd dose."

What kind of protection exercise you have until day 42?

According to data from the Pfizer and Moderna trials, protection kicked in about 14 days later the kickoff dose, when the bend showing the number of infections in the nonvaccinated group kept swinging upward while the bend for the vaccinated group did not. For both vaccines, a unmarried shot protected nigh everyone from severe illness and, as noted, was about fifty percent (Pfizer) or 80 percent (Moderna) constructive in preventing COVID altogether. Though most trial participants received their 2d vaccine on day 21 or 28, some waited until day 42, or even longer. The number of outliers is besides small to draw definitive conclusions about the impact of prolonging the two-shot regime, however. For example, of xv,208 trial participants who received the Moderna vaccine, only 81 (0.5 percent) received it outside the recommended window.

"We don't have the greatest science, at this point, to say we are 100 percent comfortable doing a booster 35, 40 days out," Denny says. "We are deferring to the public wellness concerns and the conventionalities that anything we tin do right at present is better than nothing."

If people are simply partially immunized with one dose, could that fuel more dangerous coronavirus variants?

That is a real concern, according to Paul Bieniasz, a retrovirologist at the Rockefeller University. Early in the pandemic, there was little force per unit area on the novel coronavirus to evolve because nobody's immune system was primed confronting infection, and the microbe had piece of cake pickings. Just now millions of people have become infected and take adult antibodies, so mutations that requite the virus a way to evade those defenses are rising to prominence. "The virus is going to evolve in response to antibodies, irrespective of how we administer vaccines," Bieniasz says. "The question is: Would we exist accelerating that evolution by creating land-sized populations of individuals with fractional immunity?"

Just as not finishing your entire course of antibiotics could help to fuel antibody-resistant bacteria, not getting fully vaccinated could plow your trunk into a breeding basis for antibody-resistant viruses. Only Trevor Bedford, a computational biologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center who tracks viral mutations, has tweeted that the pace of evolution is not only determined by the weakness or forcefulness of the immune system. It is also affected by the sheer number of viruses circulating in the population, he wrote. Without widespread immunizations, the latter corporeality—and the number of variants that might beget a more formidable virus—will go on to grow.

Could a longer interval between first and 2nd doses make a COVID vaccine more effective?

That result is possible. All COVID vaccines are not created equal, and the optimal dosing schedule depends on the specific design. Some vaccines are based on delicate strips of genetic material known as mRNA, some rely on hardier DNA, and others use protein fragments. These cores can be carried into a cell sheathed in a tiny lipid droplet or a harmless chimpanzee virus.

Given such differences, Denny is non surprised that the Dna-based Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine was tested and found effective with a space of 12 weeks between shots. That is nigh three to four times longer than the recommended intervals of the mRNA-based Moderna and Pfizer vaccines. In time, researchers may find that dosing schedules that are slightly dissimilar from the ones tested in the first clinical trials are more than constructive. "You could take washed dosing studies for two years, just that would not be the well-nigh responsible thing to practice in a world like this," Denny says. "Don't let the perfect be the enemy of the adept."

The author would like to acknowledge Rachel Lance for suggesting a source of data that was included in the story.

Read more about the coronavirus outbreak from Scientific American hither. And read coverage from our international network of magazines here.

Source: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/is-it-safe-to-delay-a-second-covid-vaccine-dose/

0 Response to "Is It Safe to Stay in the Plaka With Family"

Post a Comment